The concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, three kilometers away from the main camp, was the largest Nazi extermination camp. About 1.1 million people, including one million Jews were murdered there. The concentration camp was liberated by the Red Army in 1945. In 1947 the Polish parliament decided to build a memorial in Birkenau. Since 1978, Austria is represented there with an exhibition as well, in the former prison block 17. On the entrance panel to the exhibition, which evokes the German invasion in Austria, soldiers’ boots, marching over a red-white-red map, were shown. The text, below the date of March 11, 1938 read: Austria – first victim of National Socialism.

Only in 1991 did Federal Chancellor Franz Vranitzky refer in his speech at the National Assembly to another side of the story, addressing the Austrian population’s complicity in the NS crimes and thus admitting Austria’s shared responsibility in the Holocaust. Consequently, the exhibition in Auschwitz-Birkenau was repeatedly criticized and challenged. In 2009 the government decided on the redesign of the rooms and has commissioned the National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism with the coordination of its planning and execution. The National Fund was also commissioned with the renovation of block 17. That the redesign was “necessary” was evident in light of the old exhibit, according to the Fund’s Secretary General Hannah Lessing. Claire Fritsch is the Executive Director responsible for the coordination. There was a pan-European competition regarding form and content that was won, on one hand, by an exhibition team (Birgit Johler, Albert Lichtblau, Christiane Rothländer, Barbara Staudinger and Hannes Sulzenbacher) and on the other hand by the architect Martin Kohlbauer. Content as well as artistic realization have to be submitted to the museum and the International Auschwitz Council, composed by victim groups and experts. The new exhibition should focus on Austrian victims, but also address the topic of resistance in the concentration camp as well as show Austrians as perpetrators or helpers of crimes committed there.

Titled Distance. Austria and Auschwitz, four high walls are being set up, and are functioning as a projection screen for the merely virtually presented Austrian part. Objects from Auschwitz-Birkenau are show-cased in front of it. The space between the walls remains empty. Petra M. Springer spoke with Barbara Staudinger about the new exhibition.

INW: What is the meaning of the exhibition title?

Barbara Staudinger: The title Distance. Austria and Auschwitz works very well in German, because the German word distance (“Entfernung”) embodies in reality a paradox. „Ent-“ is a prefix signifying removing something [“Ferne” means distance]; “Entfernung” would thus imply removing the distance. This is however not the case, on the contrary. That is how we came up with the title, since, initially, we wanted to remove the distance through our exhibition. We want to rec-connect the stories, which started in Austria and ended in Auschwitz. We wanted to bring them closer together, remove the distance between them. The idea of “Entfernung” has, on one hand, the dimension of distance, of a spatial distance, and on the other hand it is a concept that points to the removal of individuals, who have been removed from their own country and from life. And as a third component I also see a reference to the Austrian politics of remembrance after 1945.

INW: It took a while …

B.S.: Yes, it took a while. In the main camp in Auschwitz there was, since 1978, an exhibition on National Socialism in Austria and on the Austrian victims in Auschwitz, but there was no such exhibition in Austria; the memory had been relocated to the outside, to a distance. There is Mauthausen, but there is no Holocaust Museum. Such a museum even exists in Cape Town, but it does not exist in Austria.

INW: We have long considered ourselves as victims and not as perpetrators, and this representation is thus difficult.

B.S.: In a certain sense, Austria sees itself even today as a victim. One must say, however, no matter how offensive the plaque has been, how emblematic of Austria’s appreciation, it likely had not been intended that way. The first exhibition had been conceived and realized by survivors. These survivors have indeed seen themselves as victims and they also had been the first victims. Heinrich Sussmann, a survivor of Auschwitz, was the author of the plaque’s graphic design. This is a view that Auschwitz survivors can have, and it was convenient subsequently in terms of remembrance politics. Only half of the Moscow Declaration was quoted; what is said on Austria’s responsibility has just been left out. It is not that the perpetrators were not mentioned or named in the old exhibition, they were named, but of course, in the exhibition language of that time.

INW: How is the new exhibition structured?

B.S.: There is an entrance area with two objects. On one side there is a card index by Hermann Langbein. He collected information on Auschwitz perpetrators and prisoners on index cards. He considerably helped prepare prosecution proceedings and significantly contributed to the indictment in the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial. We attempt to connect perpetrators and victims. We don’t show a victim’s history and then, at a far distance, apparently unrelated, the perpetrators. They belong together, they were together on this site, and are inherently connected to each other. Without perpetrators there would be no victims. Langbein’s index cards are a guiding object for this exhibition. Further, a large installation with remains of rails from the train station in Aspang – the deportation site in Vienna received a memorial only last year. This is the entry; then one goes through a “narrow”, a passageway of seven meters. There we show what happened after the Anschluss, that the Austrian people was torn apart on March 12, 1938, into a group that was persecuted and a group that looked away or witnessed what happened, including small and big profiteers and opportunists, perpetrators and main perpetrators. The society is torn apart on March 12, 1938, because what was formerly socially accepted antisemitism becomes the law.

The main part of the exhibition is divided into four areas. The competition’s guidelines stipulated that the exhibition should present the history of National Socialism in Austria from its beginnings until 1945, as well as the history of Austrian victims in Auschwitz until the concentration camp’s liberation. Since we wanted to connect the stories, we called the four parts Developments, Structures, Possibilities for Action and Liberation. In Developments we describe the early stages of anti-Semitism in Austria, the beginning of the NSDAP in Austria, e.g. with the movie Swastika over Austria, where one can see, already in 1932, a bursting Heldenplatz on the Gauparteitag (the party’s district reunion), or the poster When Jewish blood splashes from the knife. We also show ripped autograph cards from the desk of Hugo Bettauer, who was murdered by a Nazi in 1925. Bettauer was the author of City without Jews and held liberal views on sexuality. As a Jew and Social Democrat he represented everything that the National Socialists hated. He was shot in his editorial office, and his murderer. Otto Rothstock, took his time to tear up all letters, mail by supporters, but also threatening letters. On the side of the followers we display the diary of a Salzburg man who, out of joy about the Anschluss, had adorned it extravagantly with swastikas and newspaper clippings. There will also be a damaged Thora crown from the Währinger Synagogue on view, to illustrate the November pogrom and violence against institutions. Violence against the most holy, the Thora, meant also calling for annihilation.

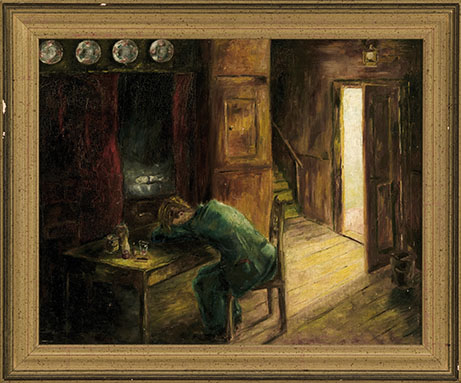

INW: There is a real part of the exhibition and a virtual one. Some objects remain in Vienna.

B.S.: All real objects that we show in the exhibition are directly related to Auschwitz or were found there. On the screens virtual, digitized 3-D footage from Austria can be seen. The stories that we tell on both levels cannot be connected 1:1. In the early stages of National Socialism, the Auschwitz concentration camp did not exist. We therefore designed the exhibition according to themes. I.e, a terror regime has to establish itself, this must occur in stages, certain developments must happen within the population, certain institutions have to be infiltrated. On the Auschwitz side, there is first the war. We show a diary by an Austrian Wehrmacht soldier who had photographed the destructions by the Wehrmacht in Poland. Then we have the first career steps of Maximilian Grabner, the Gestapo commandant in Auschwitz, who is represented with his handwritten resume – he joined the NSDAP already very early, in 1932. Walter Dejaco and Fritz Ertl were architects and had planned the extermination facilities in Auschwitz. In contrast to Grabner, they were not social climbers. Ertl studied at the Bauhaus, he also could have built something else. It shows that mass extermination too was a project of Modernity. In the Auschwitz Central Construction Office Austrians occupied important posts. The second chapter, Structures, is about how structures have evolved in Austria. And in Auschwitz: how do the Auschwitz structures affect the Austrian prisoners, or deportees from Austria? In the exhibition we show, for instance, Gestapo’s registration slips, stored in the Vienna City and State Archives. Of course we also present the Central Office for Jewish Emigration with an emigration plan that shows the pathway through the authorities. Opposite, in the real part of the exhibition, are the SS membership cards from Austrians in Auschwitz. About 250 Austrians worked for the SS in Auschwitz. 11 membership cards have subsisted. The SS tried to destroy everything when they left Auschwitz. 90% of the documents are therefore no longer available. We searched for a long time for objects regarding perpetrators in Auschwitz and found little. We were not able to establish contact to any of the perpetrators’ families, except to Fritz Ertl’s. And objects attributable to individual perpetrators do not, as far as we were informed, exist in public collections. Via the National Fund we have initiated object calls, we searched for witnesses, we tried to find people who had not testified yet. Shown are works by Franz Reiss, who, even in a French hospital in 1945, represented scenes from the concentration camp, addressing the topic of SS perpetrators and Kapos. We have searched for a long time for Austrian Kapos; They exist of course, only the objects are missing. In Auschwitz, the testimonies are collected, these are statements of survivors about Auschwitz perpetrators; there are Austrian Kapos, but no objects could be found for them. So we took the drawings by Franz Reiss, where he shows, for instance, the flogging by the Kapos. Structures also include the Auschwitz system, for instance dividing the detainees into different categories, those of privileged and and non-privileged status. In Austria, the structures were relatively clear: There were markings or surveys. Prior to the Nuremberg Laws it was not clear who was „Jewish“ and who was not. Only the National Socialist categorization made persecution possible. Anthropologists conducted surveys and photographed people. On the Hellerwiese Roma and Sinti were measured. Thousands of Viennese Jews of Polish origin were deported to the stadium to be measured there. Plaster masks were made, one is being shown. Measuring and defining were essential to the functioning of the NS structures. This resulted in identification. The system of deportations is also a very important structure, the registering of all Jewish members, then the concentration in detention camps and collective apartments, then the deportation to the concentration and extermination camps. There were 47 transports in total, which appear in the directory of the Israelite Community. Most victims were not directly deported to Auschwitz. There were only two straight transports to Auschwitz. For example, the 11-year-old girl Elfriede Balsam arrived with the big transport on July 17, 1942 and was murdered there. One of her poetry albums has been preserved. In the course of my research I have looked at several poetry albums and noticed a change over time in them. At first there were still non-Jewish friends, then some leave for Israel, they wish each other luck, they draw stars of David, they write in Hebrew, they write, we must be strong. And these are all children, who try to encourage each other.

INW: The Austrian population was actively involved. There is also the movie that Ruth Beckermann showed at the Memorial against War and Fascism.

B.S.: Yes, that is also very important and there are many photo series of these “scrub groups” which we show in the exhibition, in the narrow “passageway”, and there one sees also the onlookers and their cheerful faces. It was also important to us to show the actions of the uniformed police, who brought the Jews to the cattle cars and escorted them to Auschwitz. The witness Herbert Schrott said, at the opening of the Memorial at the Aspang station, that Austrian SS men had brought him there. “And it was the Austrians who spit on me and threw stuff after us”. Members of the National Theater came also to Auschwitz, to perform for the SS. Many more people knew, many people saw, that Auschwitz existed.

INW: And nobody wants to admit that they knew.

B.S.: Exactly. There are not only the big culprits, there were also many companies, which delivered goods, also Austrian ones. The possibility for gain existed also in Auschwitz, by robbing the deportees of their belongings, which was punished only very rarely. There was also the possibility to help, facilitated by the structure of the privileged and non-privileged. The nurse Maria Stromberger volunteered to work in the concentration camp and supported the resistance there. Norbert Loppers colleague Hans Schorr, a Viennese Communist, has saved Loppers mother from the gas chamber, because he knew the SS man. Political prisoners in particular have known people and used these connections to help. The trajectories to Auschwitz were important to us. Theresienstadt, one of the transit stops, is significant. We have a boxcar-slip for Helga Pollak-Kinsky, when she was deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz. Many had been in Theresienstadt, but also in Buchenwald or Litzmannstadt, or had come via Drancy or other ways, such as Heinz Geiringer, whose story resembles that of Anne Frank. The family had escaped from Vienna to Amsterdam and was hiding, in close proximity to Anne Frank, the families knew each other. While Anne Frank wrote in her diary, Heinz Geiringer painted. We show a self-portrait that he painted in his hiding place. Both pictures were hidden, together with a letter by the father, underneath the flooring planks. The Geiringers were discovered as well and deported to Auschwitz. Mother and daughter survived. The mother married Anne Frank’s father after the war.